My academic coordinates lie at the intersection of primatology/biological anthropology, environmental anthropology, and conservation. I am interested in primate behavioral flexibility in the face of anthropogenic pressures, how humans fit into a broader primate community ecology, the causes and consequences of ecological sympatry between humans and other primates, and what human-primate relationships tell us about what it means to be human and what it means to be a primate.

Primary research areas

- Primate behavioral and ecological flexibility in human-modified landscapes

- Ethnoprimatology

- Ecological & social impacts of human-primate interactions

- Crop feeding behavior: primate and human perspectives

- Human dimensions of human-primate interactions and conflict

- Primate conservation education

- Ethics of field primatology

- Integrative anthropology: reconciling biological and sociocultural anthropology

Study species & sites

Since 2010, I have primarily been conducting research on the human-primate interface in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, with moor macaques (Macaca maura). I have also conducted field research on the following primate species:

- Macaca tonkeana: Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Macaca ochreata: Farumpenai Nature Reserve, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Rhinopithecus brelichi: Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve, China

- Macaca mulatta: Silver Springs State Park, Florida, USA

Projects

People, primates, and tropical forests: Integrated primatological and ecological research to advance human-primate coexistence and ecosystem health in Indonesia

Funded by the National Science Foundation (Award #2153614), this project provides opportunities for a total of 15 U.S. students from San Diego State University to engage in a 6-week long international field research experience focused on human-primate coexistence and ecosystem health in Sulawesi, Indonesia. This project will expand the diversity of the STEM workforce by recruiting student participants from underrepresented groups. Drawing from the expertise in primatology and tropical ecology of the PI and foreign mentor, students will conduct research that will advance our understanding of how primates adapt to human-induced environmental change, with implications for ways for people and primates to coexist, and how human activities affect the health of tropical ecosystems. Student participants will learn how to write a research proposal and carry out independent field research. Students will also benefit from the fieldwork experience in terms of personal growth and maturity and the development of invaluable life skills, such as interpersonal and cross-cultural communication. This international research experience will produce cohorts of students who are better prepared for research and for employment in increasingly multicultural workplace environments. It will also help increase the diversity of ideas and perspectives on ways to advance ecosystem health and the sustainable coexistence of humans and wildlife.

Moor macaque decision-making in a human-induced landscape of fear

In the contemporary era it is becoming increasingly difficult to find a primate population that has not experienced some form of anthropogenic influence. Primates living in anthropogenic spaces may benefit from access to novel food resources, such as agricultural crops or provisioned foods, but they also must deal with potential negative outcomes from the presence of humans and their activities. These primates, therefore, face a risk-reward tradeoff and may be experiencing a “landscape of fear.” Our understanding of how primates balance risks and rewards in such environments, however, remains limited, particularly with regard to group decision making on when and where to move and forage. The goal of this project is to investigate how a human-induced landscape of fear affects foraging and movement decisions of the endangered moor macaque (Macaca maura) in Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, Sulawesi, Indonesia. This project is funded by the National Science Foundation (Award #2222891).

Expanding local capacity in methods in primate behavior, ecology, and conservation in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

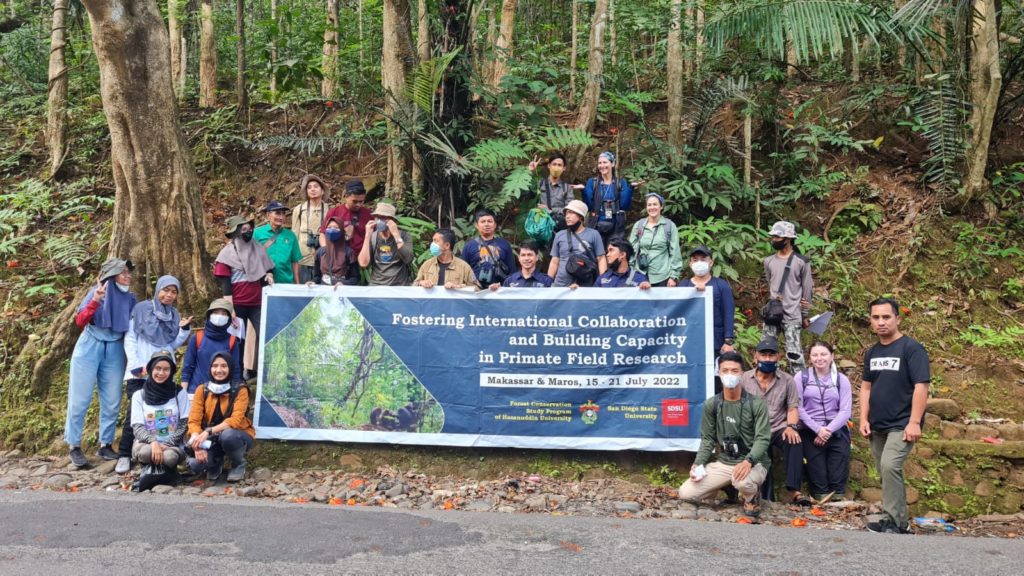

Indonesia supports the richest primate fauna of any Asian country, thereby making it a high priority for conservation efforts. Although greater attention is being paid to primate conservation in Indonesia, there remains a dearth of expertise in primate ecology, behavior, and conservation, particularly in eastern Indonesia, such as the island of Sulawesi. The objective of this project is to provide training in field methods in primatology and conservation to local university students and wildlife professionals (i.e., national park, forestry department, and non-governmental organization staff) in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The training will involve a 10-day workshop consisting of daily lectures, field exercises in primate behavior and ecology, and conservation education activities at Hasanuddin University and Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Lecture topics will include an introduction to the primates and primate behavior and ecology, methods in field primatology, the human-primate interface, and conservation and management strategies. Field exercises will enable participants to gain hands-on experience conducting systematic behavioral observations, line-transect sampling, habitat analysis, camera trapping, GPS/GIS analysis, and conservation education outreach. This project will help build local students’ and wildlife professionals’ skillsets, thereby enabling them to spearhead their own research projects and conservation and management plans for South Sulawesi’s endemic and Endangered moor macaque (Macaca maura) and its habitat. This project has been funded by Primate Conservation, Inc. and a Small Conservation Grant from the American Society of Primatologists.

Whose woods are these?: Human-wildlife conflict and biodiversity conservation in Sulawesi, Indonesia

I have been awarded a 2021 Student-Faculty Fellowship grant from ASIANetwork for my project titled “Whose woods are these?: Human-wildlife conflict and biodiversity conservation in Sulawesi, Indonesia.” This grant will provide three SDSU undergraduate students an opportunity to gain practical knowledge of this contemporary issue via an immersive field experience in Indonesia alongside myself and my local partners. Fieldwork activities will include: lectures and meetings with faculty and leaders of governmental and non-governmental organizations focused on sustainable development and biodiversity conservation, and field training modules in primate/wildlife ecology, ethnographic research methods, and conservation education methods. SDSU students will be paired with Indonesian university students and will work collaboratively, using digital technologies, to create educational tools to inform conservation education outreach efforts and the management of human-wildlife conflict in the area. Through this project, SDSU students will develop critical skills needed to become successful researchers and global citizens, as well as invaluable life skills, such as interpersonal and cross-cultural communication.

Three SDSU students (Melissa Callado, Pedro Rios, and Jadyn Skipper) and I traveled to Indonesia in July 2022 for this project. Click here to read about our trip!

Ecological and social impacts of human-primate interactions and provisioning

With funding from SDSU’s University Grants Program and the President Leadership Fund, my students (Kristen Morrow and Josh Trinidad) and I have examined how provisioning and interacting with people affects primate ranging and social behavior. The target population of this project includes moor macaques and the people who encounter them in Bantiumurung-Bulusaraung National Park, Sulawesi, Indonesia. One of our study groups has been habituated to human presence for many years, but it has never been observed interacting with people traveling on the provincial road that intersects the park. However, beginning in late 2015, this group began spending a considerable portion of the day along the road, with some individuals accepting food from people and foraging in trash pits. These behaviors are risky in that they increase the likelihood of them being hit by passing cars and motorcycles and the potential for human-primate disease transmission. We found that males, both adult and subadult, were more likely to be on the road compared to females. However, individuals who were along the road were not more likely to be in close proximity to others, which indicates that they do not perceive the road to be a risky context, even though risk of injury and/or death from passing vehicles is a reality. We also found that the group was less cohesive when along the road compared to when they are in the forest, which suggests that being on the road and interacting with people disrupts typical social relationships. By examining this emerging human-primate interface, our goal is to contribute to a growing body of research focused on how roads, an increasingly pervasive element of anthropogenic infrastructural expansion, affect wildlife and ecosystems (“road ecology”). We are also using the project results to develop conservation education programs focused on expanding people’s knowledge of the negative effects of provisioning (e.g., poor nutrition, possibility of disease transmission, increased social conflicts, risk of injury) and why protecting the macaques is important (e.g., for the roles primates play in forest regeneration).

Ecological correlates of crop feeding by moor macaques

Crop feeding (or crop raiding) – the consumption of cultivated foods produced in agricultural areas – is an increasingly common response by wildlife to anthropogenic habitat change, and is particularly pervasive among primates. Because of the detrimental impact crop raiding can have on human livelihoods and the likelihood of local support for conservation efforts, crop raiding by primates has become one of most serious challenges to primate conservation. With funding from SDSU’s University Grants Program and the American Institute for Indonesian Studies (AIFIS), my graduate student, Alison Zak, and I are addressing this growing concern by integrating ecological, nutritional, and ethnographic analyses of the causes of crop feeding behavior by moor macaques (Macaca maura), an endangered primate species endemic to Sulawesi, Indonesia. The results of this project will inform the development of crop raiding mitigation strategies for rural farmers across Sulawesi, Indonesia, which if successful, will increase local Crop feeding – the consumption of cultivated foods produced in agricultural areas – is an increasingly common response by wildlife to anthropogenic habitat change, and is particularly pervasive among primates. Because of the detrimental impact crop feeding can have on human livelihoods and the likelihood of local support for conservation efforts, crop raiding by primates has become one of most serious challenges to primate conservation. With funding from SDSU’s University Grants Program and the American Institute for Indonesian Studies (AIFIS), my former graduate student, Alison Zak, and I, addressed this growing concern by integrating ecological, nutritional, and ethnographic analyses of the causes of crop raiding behavior by moor macaques (Macaca maura), an endangered primate species endemic to Sulawesi, Indonesia. Using camera trap technology and by conducting interview with farmers, we found that farmer’s perceptions of crop feeding behavior by macaques do not always align with patterns determined by the camera traps. We communicated these results back to farmers to assist farmers in crop feeding mitigation efforts.

The intersubjectiveness of primate habituation

This project examined a facet of the human-primate interface that remains largely unexplored from an ethnoprimatological perspective: habituation. Defined as the process by which wild animals accept human observers as a neutral element in their environment, habituation is one of the hallmarks of field primatology. Although primatologists have explored how to accomplish habituation, little attention has been paid to habituation as a relational and mutually modifying process that occurs between human observers and their primate study subjects. With funding from the Wenner-Gren Foundation, my graduate student, KT Hanson, and I used a hybrid approach, drawing from ethnoprimatology and perspectives in human-animal studies, to examine the habituation of moor macaques (Macaca maura) as both a scientific and intersubjective process. Integrating ethological measures with ethnographic material enabled us to: explore how and why quantitative markers of habituation “success” differ from subjective impressions, observe habituation—and primate fieldwork in general—as a bidirectional, intersubjective experience, and come to understand habituation as a dynamic spectrum of tolerance rather than a state to be “achieved.” Collectively, our findings have important implications for future work in ethnoprimatology and habituation methodology, as well as the practice of primate fieldwork.

The human-macaque interface along the Silver River, Florida

Beginning in 2012, my colleagues and I initiated a project on the interface between boaters and a free-ranging population of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) along Florida’s Silver River funded by a National Geographic Society/Waitt grant. Our goal was to take advantage of the unique opportunity presented by the historical introduction of Asian rhesus monkeys to the riparian woodlands of north central Florida to study primate ecological and behavioral flexibility and the nature of interactions human and nonhuman primates in the U.S. wilderness. My former graduate student, Tiffany Wade, and I focused on documenting the feeding ecology of the macaques and their interactions with people along the river’s edge. We found that Silver River macaques exhibited a dietary strategy similar to congeners in temperate broadleaf forests in Asia: they consumed more leaves and other non-fruit vegetative parts compared to fruits. They have also incorporated locally available plants native to North America into their dietary repertoire, such as sedges. This project not only contributes to our understanding of primate ecological flexibility, but also provides critical data needed for the management of the human-macaque interface at this site.